Mass-to-charge ratio

|

|

|

| SI quantity dimension: | M/(I⋅T) |

| SI unit: | kg/C |

| other units: | Th |

The mass-to-charge ratio ratio (m/Q) is a physical quantity that is widely used in the electrodynamics of charged particles, e.g. in electron optics and ion optics. It appears in the scientific fields of lithography, electron microscopy, cathode ray tubes, accelerator physics, nuclear physics, Auger spectroscopy, cosmology and mass spectrometry.[1] The importance of the mass-to-charge ratio, according to classical electrodynamics, is that two particles with the same mass-to-charge ratio move in the same path in a vacuum when subjected to the same electric and magnetic fields.

Some fields use the charge-to-mass ratio (Q/m) instead, which is the multiplicative inverse of the mass-to-charge ratio. The 2006 CODATA recommended value is e⁄me = 1.758820150(44)×10^11 C/kg.[6].

Contents |

Origin

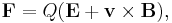

When charged particles move in electric and magnetic fields the following two laws apply:

-

(Lorentz force law)

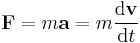

(Newton's second law of motion)

where F is the force applied to the ion, m is the mass of the particle, a is the acceleration, Q is the electric charge, E is the electric field, and v x B is the cross product of the ion's velocity and the magnetic field.

This differential equation is the classic equation of motion for charged particles. Together with the particle's initial conditions, it completely determines the particle's motion in space and time in terms of m/Q. Thus mass spectrometers could be thought of as "mass-to-charge spectrometers". When presenting data in a mass spectrum, it is common to use the dimensionless m/z, which denotes the dimensionless quantity formed by dividing the mass number of the ion by its charge number.[1]

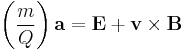

Combining the two previous equation yields:

.

.

This differential equation is the classic equation of motion of a charged particle in vacuum. Together with the particle's initial conditions it determines the particle's motion in space and time. It immediately reveals that two particles with the same m/Q ratio behave in the same way. This is why the mass-to-charge ratio is an important physical quantity in those scientific fields where charged particles interact with magnetic or electric fields.

Exceptions

There are non-classical effects that derive from quantum mechanics, such as the Stern–Gerlach effect that can diverge the path of ions of identical m/Q.

Symbols and units

The IUPAC recommended symbol for mass is m.[2] The IUPAC recommended symbol for charge is Q;[3] however,  is also very common. Charge is a scalar property, meaning that it can be either positive (+ symbol) or negative (- symbol). Sometimes, however, the sign of the charge is indicated indirectly. Coulomb is the SI unit of charge; however, other units are not uncommon.

is also very common. Charge is a scalar property, meaning that it can be either positive (+ symbol) or negative (- symbol). Sometimes, however, the sign of the charge is indicated indirectly. Coulomb is the SI unit of charge; however, other units are not uncommon.

The SI unit of the physical quantity  is kilograms per coulomb.

is kilograms per coulomb.

![[m/Q]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/13dcc9dc07b2f5388f9fe2153a94583d.png) = kg/C

= kg/C

Mass spectrometry

The units and notation above are used when dealing with the physics of mass spectrometry; however, the unitless m/z notation is used for the independent variable in a mass spectrum. This notation eases data interpretation since it is numerically more related to the unified atomic mass unit of the analyte.[1] The m in m/z is representative of molecular or atomic mass and z is representative of the number of elementary charges carried by the ion. Thus a molecule of 1000 Da carrying two charges will be observed at m/z 500. These notations are closely related through the unified atomic mass unit and the elementary charge.

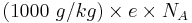

Although it is rarely done the numerical conversion factor from SI units (kg/C) to m/z notation is:

where

History

In the 19th century the mass-to-charge ratios of some ions were measured by electrochemical methods. In 1897 the mass-to-charge ratio, [m⁄e], of the electron was first measured by J. J. Thomson.[4] By doing this he showed that the electron—postulated earlier to explain electricity—was in fact a particle with a mass and a charge; and that its mass-to-charge ratio was much smaller than that of the hydrogen ion H+. In 1898 Wilhelm Wien separated ions (canal rays) according to their mass-to-charge ratio with an ion optical device with superimposed electric and magnetic fields (Wien filter). In 1901 Walter Kaufman measured the relativistic mass increase of fast electrons. In 1913, Thomson measured the mass-to-charge ratio of ions with an instrument he called a parabola spectrograph.[5] Today, an instrument that measures the mass-to-charge ratio of charged particles is called a mass spectrometer.

Charge-to-mass ratio

The charge-to-mass ratio (Q/m) of an object is, as its name implies, the charge of an object divided by the mass of the same object. This quantity is generally useful only for objects that may be treated as particles. For extended objects, total charge, charge density, total mass, and mass density are often more useful.

Significance

In some experiments, the charge-to-mass ratio is the only quantity that can be measured directly. Often, the charge can be inferred from theoretical considerations, so that the charge-to-mass ratio provides a way to calculate the mass of a particle.

Often, the charge-to-mass ratio can be determined from observing the deflection of a charged particle in an external magnetic field. The cyclotron equation, combined with other information such as the kinetic energy of the particle, will give the charge-to-mass ratio. One application of this principle is the mass spectrometer. The same principle can be used to extract information in experiments involving the Wilson cloud chamber.

The ratio of electrostatic to gravitational forces between two particles will be proportional to the product of their charge-to-mass ratios. It turns out that gravitational forces are negligible on the subatomic level. This is due to the extremely small masses of the subatomic particles.

The electron

The elementary charge-to-electron mass quotient, e⁄me, is a quantity in experimental physics. It matters because the electron mass me is difficult to measure directly, and is instead derived from measurements of the elementary charge e and e⁄me. It also has historical significance: the Q/m ratio of the electron was successfully calculated by J. J. Thomson in 1897—and more successfully by Dunnington, which involves the angular momentum and deflection due to a perpendicular magnetic field. Thomson's measurement convinced him that cathode rays were particles, which were later identified as electrons, and is generally credited with their discovery.

The 2006 CODATA recommended value is e⁄me = 1.758820150(44)×1011 C/kg.[6] CODATA refers to this as the electron charge-to-mass quotient, but ratio is still commonly used.

There are two other common ways of measuring the charge to mass ratio of an electron, apart from Thomson and Dunnington's methods.

- The Magnetron Method: Using a GRD7 Valve (Ferranti valve), electrons are expelled from a hot tungsten-wire filament towards an anode. The electron is then deflected using a solenoid. From the current in the solenoid and the current in the Ferranti Valve, e/m can be calculated.

- Fine Beam Tube Method: Electrons are accelerated from a cathode to a cap-shaped anode. The electron is then expelled into a helium-filled ray tube, producing a luminous circle. From the radius of this circle, e/m is calculated.

Zeeman Effect

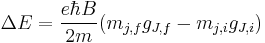

The charge-to-mass ratio of an electron may also be measured with the Zeeman effect, which gives rise to energy splittings in the presence of a magnetic field B:

Here mj are quantum integer values ranging from -j to j, with j as the eigenvalue of the total angular momentum operator J, with

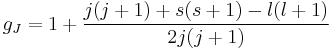

where S is the spin operator with eigenvalue s and L is the angular momentum operator with eigenvalue l. gJ is the Landé g-factor, calculated as

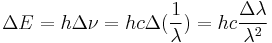

The shift in energy is also given in terms of frequency ν and wavelength λ as

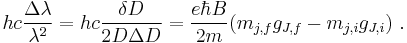

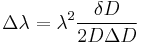

Measurements of the Zeeman effect commonly involve the use of a Fabry–Pérot interferometer, with light from a source (placed in a magnetic field) being passed between two mirrors of the interferometer. If δD is the change in mirror separation required to bring the mth-order ring of wavelength λ + Δλ into coincidence with that of wavelength λ, and ΔD brings the (m + 1)th ring of wavelength λ into coincidence with the mth-order ring, then

.

.

It follows then that

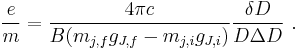

Rearranging, it is possible to solve for the charge-to-mass ratio of an electron as

References

- ^ a b c IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "mass-to-charge ratio, m/z in mass spectrometry".

- ^ International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (1993). Quantities, Units and Symbols in Physical Chemistry, 2nd edition, Oxford: Blackwell Science. ISBN 0-632-03583-8. p. 4. Electronic version.

- ^ International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (1993). Quantities, Units and Symbols in Physical Chemistry, 2nd edition, Oxford: Blackwell Science. ISBN 0-632-03583-8. p. 14. Electronic version.

- ^ Philosophical Magazine, 44, 293 (1897). lemoyne.edu

- ^ Proceedings of the Royal Society A 89, 1-20 (1913) [as excerpted in Henry A. Boorse & Lloyd Motz, The World of the Atom, Vol. 1 (New York: Basic Books, 1966)] lemoyne.edu

- ^ NIST Database [1].

Bibliography

- Szilágyi, Miklós (1988). Electron and ion optics. New York: Plenum Press. ISBN 0-306-42717-6.

- Septier, Albert L. (1980). Applied charged particle optics. Boston: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-014574-X.

- International vocabulary of basic and general terms in metrology =: Vocabulaire international des termes fondamentaux et généraux de métrologie. International Organization for Standardization. 1993. ISBN 92-67-01075-1.CC.

- IUPAP Red Book SUNAMCO 87-1 "Symbols, Units, Nomenclature and Fundamental Constants in Physics" (does not have an online version).

- Symbols Units and Nomenclature in Physics IUPAP-25 IUPAP-25, E.R. Cohen & P. Giacomo, Physics 146A (1987) 1-68.

External links

- BIPM SI brochure

- AIP style manual

- NIST on units and manuscript check list

- Physics Today's instructions on quantities and units